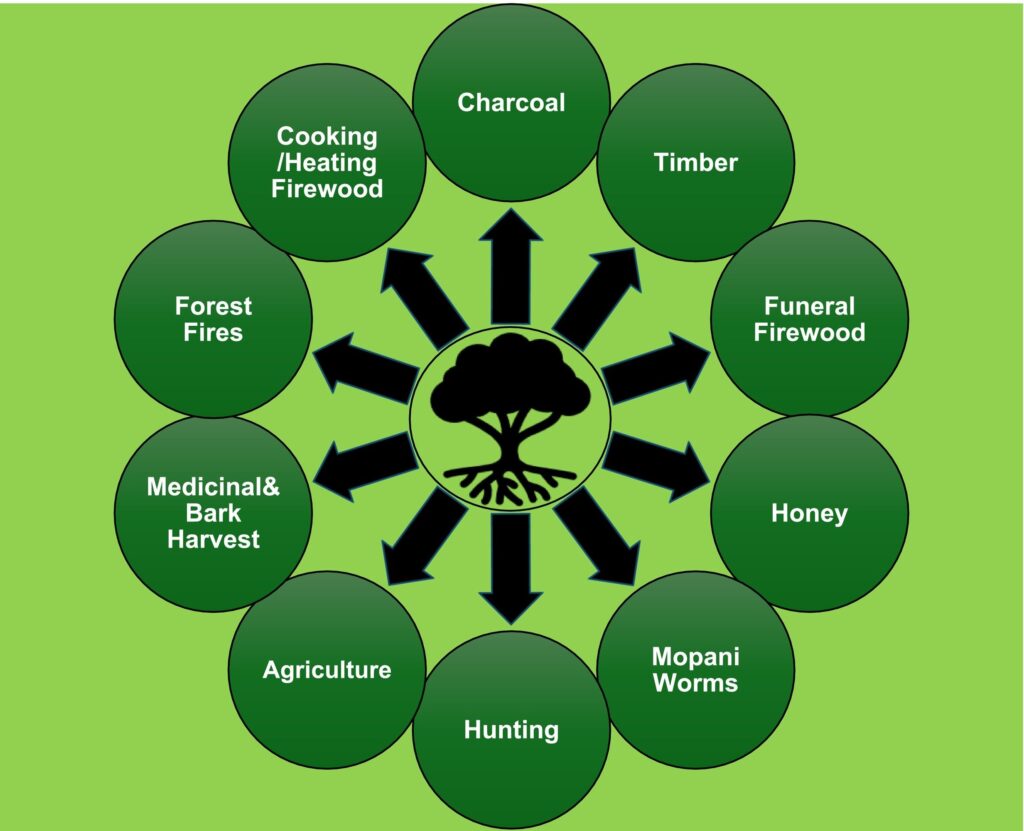

Main and secondary (subtle) factors of deforestation. Credit: Energy Research and Social Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.erss.2025.104389

Across rural Zambia, small solar home systems and lanterns have transformed daily life. From 2018 to 2022, more than 1 million small solar power generation devices were sold nationwide. These range from small solar lanterns to home kits that can power your radio, TV and mobile phone charger.

Children can study after dark, cell phones stay charged, and families are no longer completely dependent on smoky kerosene lamps.

However, these solar power systems do not receive funding or subsidies from governments or development finance institutions. And affordable credit for rural people to purchase clean energy is rare. The purchase of small solar power systems puts new financial pressure on households to pay for long-term installment plans.

I am pursuing a Ph.D. He was involved in the implementation and management of renewable energy in rural areas and was part of a team of researchers in sustainable energy, environmental research and rural green transitions. We investigated how rural forest communities in Zambia pay for solar power, and how this affects the long-term use of their forests.

We interviewed 80 people and conducted 10 focus group discussions over 28 months in the Mkushi, Kapiri, Mposhi, Chongwe and Luano regions of Zambia. Together, these areas are home to approximately 700,000 people. However, they have minimal access to the national electricity grid. Most households rely on firewood or charcoal for energy.

Our research shows that people pay for solar power by cutting down trees and overharvesting forest products.

Once a miombo forest area rich in mopaneworm, mtondo (wild mango) and other fruit trees, these forests have now been thinned and patchy. Our interviewees described forest loss, and our own geospatial analysis of forest cover loss from 2001 to 2023 in the same region confirmed this.

While deforestation has always been present in rural Zambia, our research shows that it has intensified due to the rapid promotion and adoption of solar power technology and the need to generate regular income to cover monthly payments.

Tree decline is not only an ecological problem, but also a social problem. As trees are lost, firewood collection becomes more difficult, wild food becomes more scarce, and rural areas lose a critical buffer against climate change.

This requires affordable, innovative and inclusive financing models that do not force households to exploit forests to meet monthly payments.

Solar loans are causing forest loss

More than 85% of participants reported financing their solar power purchases with income from the sale of charcoal, wood, honey, and other forest products sourced from natural dyke forests.

One charcoal burner told us: “Times are tough, the demand for charcoal is so high that the number of suitable trees is decreasing. Therefore, we have no choice but to start cutting down even useful trees such as fruit trees and medicinal trees.”

“We produce charcoal, but it’s for sale so we hardly ever use it for cooking. We all here rely on firewood…Charcoal is for the wealthy…(lol)”, said one person.

Another person we interviewed collects wild honey from the forest and sells it. they told us: “…2.5 liters (of honey) sells for US$15 (K300) and natural honey is always in high demand…It supported me and helped me buy a good bicycle, household items and even pay off my solar loan.”

In Mukushi, a woman who collects and sells mopane worms, a seasonal delicacy, said. “I sell the worms for US$25 (K500) per 20-litre container. In good seasons, I can raise a lot of money…I have no trouble buying uniforms for my children, essentials, nice phones, radios and solar power.”

However, people who previously used forests sustainably reported that they were now forced to engage in harmful practices to pay the monthly installments. For example, honey harvesters explained that they cut off branches that supported beehives, whereas previously they had carefully sucked out the bees and collected honey without damaging the trees.

Others mentioned stripping bark to make rope, digging up medicinal roots, and clearing forests to expand small farms as soil fertility declines.

The paradox of clean energy and forest finance

Solar power technology itself is not responsible. The problem lies in the method of raising funds. Users typically make a small down payment of 10% to 15% of the cost to take the system home, and then pay the system back over 1 to 3 years. If you miss even one monthly payment, your solar system will be locked and you will no longer be able to use it.

For communities living near forests, the only way to earn enough income to pay for regular solar power is to use more forest than before and sell forest resources.

The problem lies in a huge policy gap. Energy plans focus on expanding access to solar power, but little consideration is given to how households will pay for the system. Forest conservation efforts cannot meet rural energy needs. While solar vendors are pushing market growth and conservation groups are promoting tree planting, local communities are caught in the middle, deploying clean energy while financing energy in ways that harm the environment.

In many regions, traditional leaders and local officials who are supposed to regulate forest use sell charcoal themselves. This blurs responsibility and makes it difficult to sustain community-led conservation efforts.

Inequalities are also to blame. Wealthy families and farmers can afford to buy solar power systems outright. Poor families, especially those living in areas adjacent to forests, often have no choice but to derive value from their surrounding environment. These choices are not made out of ignorance, but out of necessity.

what needs to happen next

We need comprehensive financing that offers affordable and flexible payment options, including loans, grants, and pay-as-you-go models tailored to rural income cycles.

As COP30, the global climate change summit, approaches, world leaders should prioritize green energy for forest-adjacent communities that previously lacked access to national electricity grids.

COP30 should address targeted solar subsidies, microcredits and community energy schemes so that rural people across Africa who purchase solar PV systems do not have to rely on forest revenues to pay for them. COP30 could also increase research funding to understand and address the relationship between rural energy access and deforestation. With this support, these communities finally have access to clean electricity without sacrificing their forests.

Zambia’s Ministry of Energy and Environment must also urgently work together to ensure that the expansion of solar power generation in rural areas does not occur at the expense of forests.

Deforestation in rural Zambia has multiple causes, and the introduction of solar power is only one of them. However, it is important because it reflects a structural gap in development planning.

Solar power is one of the most promising tools to address energy poverty in sub-Saharan Africa. But sustainability must be measured not only by the cleanliness of the technology, but also by the way it is acquired and maintained.

Presented by The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Citation: COP30: Zambia’s forest communities need funding for solar power so they don’t have to cut down trees to pay for it (November 17, 2025) Retrieved November 17, 2025 from https://techxplore.com/news/2025-11-cop30-zambia-forest-communities-solar.html

This document is subject to copyright. No part may be reproduced without written permission, except in fair dealing for personal study or research purposes. Content is provided for informational purposes only.