Just before a bankruptcy judge was expected to approve the sale of Luminar’s lidar business, an unidentified party submitted a bid that apparently blew the top price of $33 million.

The bid, which surfaced just before Tuesday’s public hearing, set off a series of rapid-fire meetings between Luminar’s remaining management team, its lawyers, the “special transaction committee” created to navigate the bankruptcy process, and ultimately the company’s entire board of directors.

Luminar’s lawyers said that while the bid was “significantly higher,” the offer was “flawed.” The company ultimately decided to stick with the $33 million bid it received from MicroVision in Monday’s auction.

The identity of the person who submitted the unlikely offer has not been disclosed, but Luminar’s lawyers said it was an “insider acquirer” and likely came from the company’s founder, Austin Russell.

Russell was already looking to buy the company late last year, before it fell into bankruptcy (and after abruptly stepping down as CEO). Representatives from his new company, Russell AI Labs, previously told TechCrunch that they were interested in bidding for the lidar business during the bankruptcy case. (The same representatives did not respond to requests for comment Wednesday.)

The hearing proceeded and the sale to MicroVision was approved. The sale of Luminar’s semiconductor division to a company called Quantum Computing Inc. was also approved.

The deal is likely to close in the coming weeks, after which the company will cease to exist, ending one of the most talked-about suppliers of the nascent self-driving car era.

tech crunch event

san francisco

|

October 13-15, 2026

What MicroVision wants

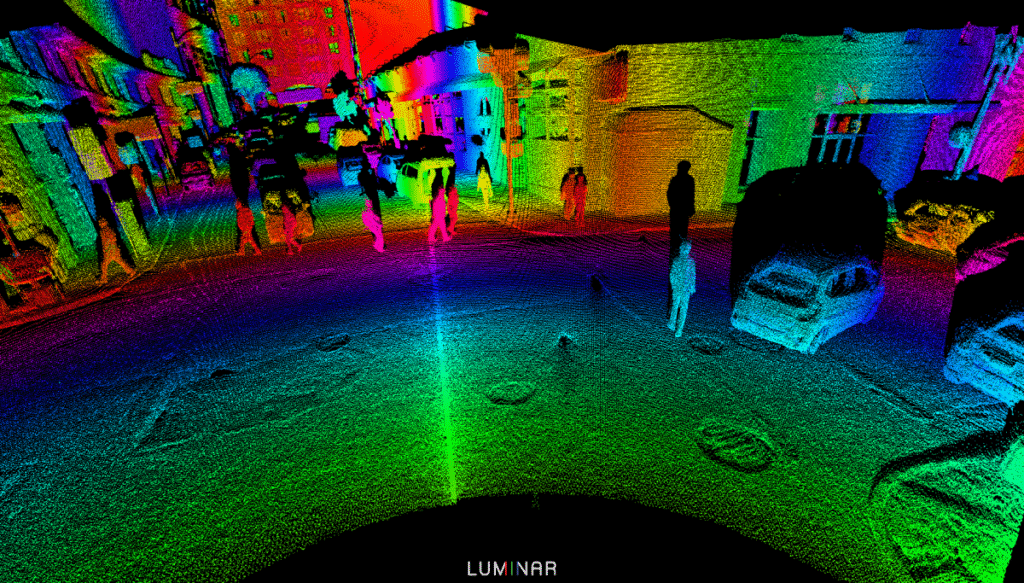

CEO Glenn DeVos said MicroVision will continue Russell’s goal of using lidar to help cars drive themselves. As part of the asset sale, MicroVision will acquire Luminar’s lidar technology and remaining staff, and said it expects other people who were laid off before the bankruptcy to join the company.

For DeVos, Luminar’s LIDAR technology is what MicroVision was missing from his company’s portfolio. The Redmond, Wash.-based company doesn’t have the same name recognition as leaders in the lidar space like Aeva, Innoviz, Hesai, and Ouster, in part because it lacks long-range sensing capabilities that are critical to cars.

In an interview with TechCrunch, DeVos said MicroVision has a “very strong” software team and an equally strong short-range lidar team. But DeVos, who took over as CEO of MicroVision last year after a long career at auto suppliers Delphi and Aptiv, wants to expand beyond its current markets of industrial applications, security and defense.

“So when we looked at the Luminar engineering team and what they were doing, we said, ‘From an engineering capability standpoint, this is a great compliment,'” DeVos said. “This is very important in this space in terms of winning the car business.”

DeVos said he hopes Microvision can take advantage of Luminar’s existing commercial contracts with automakers, even tattered ones like the one with Volvo, and use them as stepping stones into the automotive space, which will be a huge new potential source of revenue for his company.

“I’ve been in the auto industry a long time. I’ve had experiences where contractual relationships went off the rails and I basically worked very hard to get them back on track. We’re going to look at each one of them. We don’t assume any of them are beyond preservation,” he said. “We never want to get to that point, but you know, there are ways to put these pieces back together.”

The second mysterious bidder?

Although approval of the sale is behind him, Tuesday’s offer was not the first time DeVos and MicroVision have faced off against a mystery bidder.

During the hearing, Luminar’s attorney and Jefferies managing director Rich Morgner, who was assisting in the sale process, revealed that another unidentified party had made bids dating back to Jan. 12.

Mr Morgner said there were problems with the bid from the beginning. Initially, the party’s funding came from “Chinese state-owned enterprises.” When Luminar raised concerns about regulatory approvals, Morgner said the bidder replaced the financing with three different sources outside of China.

“One was a family fund, which we were finally able to confirm. The second was a Cayman Islands-based SPV whose stock statements showed an approximate number of funds. There was also a family office in Europe, which was also part of the loan syndicate,” he said.

Although lawyers and bankers were able to prove that the “family money” was reliable, Morgner said the Cayman Islands SPV’s large ballpark numbers looked questionable.

“What I was worried about was the money coming in… [so] Money may come. “It wasn’t like looking at long-dated securities statements where you could see the rise and fall of various securities,” he said, adding that evidence of funds from European family office sources was also never provided.

Luminar’s lawyers did not disclose the identity of the bidder or whether it was the same party that submitted the bid that disrupted Tuesday’s public hearing.