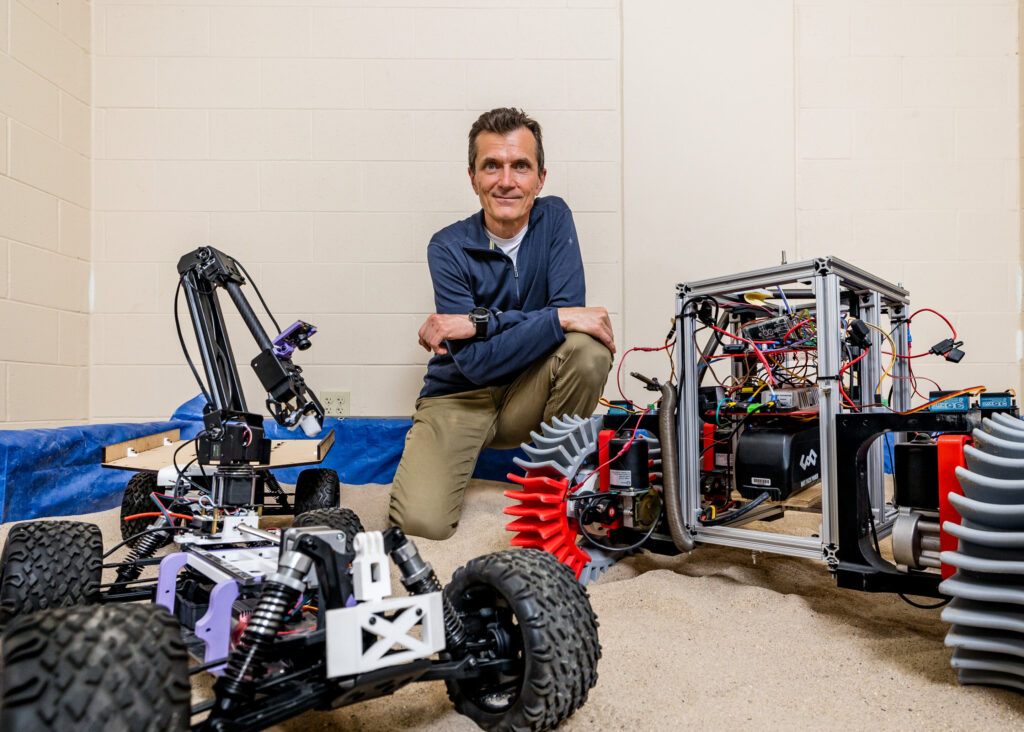

Professor Dan Negurt, a professor of mechanical engineering, will pose on the Space Rover used for testing. Credit: Joel Hallberg/UW – Madison

When millions of dollars extraterrestrial vehicles are stuck in soft sand and gravel just like Mars’ Rover Spirit in 2009, Earth-based engineers take over like a virtual tow truck, moving wheels, overturning the course with delicate and time-consuming efforts, and publishing a series of courses that continue their exploratory mission.

Spirit has remained stuck forever, but in the future, better topography testing at Terra Pharma could help avoid these heavenly crises.

Using computer simulations, mechanical engineers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison revealed flaws in how rovers are tested on Earth. That error leads to an overly optimistic conclusion about how the rover will behave after it is deployed on an extraterrestrial mission.

A key element in preparing for these missions is to understand exactly how rovers cross extraterrestrial surfaces with low gravity to prevent them from getting stuck in soft terrain or rocky areas.

On the moon, gravity pull is six times weaker than Earth. For decades, researchers testing rovers have explained the difference in gravity by creating prototypes that are one-sixth the mass of a real rover. They test these lightweight rovers in the desert and observe how they gain insight into how they move across the sand and how it works on the moon.

However, it turns out that this standard testing approach overlooked seemingly insignificant details. The pull of Earth’s gravity against the sands of the desert.

The operation of the rover is simulated with Project Chrono, an open source physics simulation engine developed with UW-Madison. Credit: Dan Negrut / UW – Madison

Through the simulation, Dan Negurt, professor of mechanical engineering at UW-Madison, and his collaborators determined that Earth’s gravity would pull down sand much stronger than Mars and the Moon. On Earth, sand is harder and more supportive, reducing the likelihood of shifting under the wheels of a vehicle. However, the surface of the moon is “fluffy” and therefore shifts more easily. This means that rovers have low traction and can hinder mobility.

“Looking back, the idea is simple. Not only does it pull the rover’s gravity, but the effects of the gravitational force on the sand also need to have a better grasp of how the rover works on the moon,” says Negurt. “Our findings highlight the value of analyzing rover mobility in granular soils using physics-based simulations.”

The team recently detailed the findings from the Journal of Field Robotics.

The researchers’ discoveries stem from work on a NASA-funded project to simulate a Viper Rover planned for the lunar mission. The team worked with Italian scientists to leverage Project Chrono, an open-source physics simulation engine developed with UW-Madison. The software allows researchers to quickly and accurately model complex mechanical systems, such as “squeeze” sand and full-size rovers that operate on soil surfaces.

While simulating the Viper Rover, they noticed a discrepancy between Earth-based test results and simulations of the mobility of the lunar rover. A deeper dig in the Chrono simulation revealed flaws in the test.

The benefits of this research go far beyond NASA and space travel. For applications on Earth, Chronos are used by hundreds of organizations and have a better understanding of complex mechanical systems, from precision mechanical clocks to US military trucks and tanks operating in off-road conditions.

Hug on the sand in a simulation-based engineering lab. Credit: Joel Hallberg/UW – Madison

“It’s rewarding that our research is very relevant to solving many real-world engineering challenges,” says Negurt. “We are proud of what we have achieved. As a university lab, it is extremely difficult to get the industrial strength software used by NASA.”

While Chrono is free and open to use worldwide, the UW-Madison team is doing important and continuous work to develop and maintain the software and provide user support.

“It’s very rare in academia to produce software products at this level,” says Negurt. “There are certain types of applications related to NASA and planetary exploration. Simulators can solve problems other tools, including simulators from large tech companies, cannot solve. It’s exciting.”

Because Chrono is open source, Negurut and his team are focusing on continually innovating and enhancing the software to stay relevant.

“All our ideas are in the public domain and competition can quickly adopt them, which will help us continue to move forward,” he says. “We have been able to receive support from the NSF, the US Army Laboratory and NASA for the past decade.”

Co-authors of the paper include Waifu from Shanghai Ziaoton University, Pei Li and Arno Rogg from UW-Madison, Alexander Schepelmann from NASA, Protoinnovations, Samuel Chandler from LLC, and Ken Kamrin from MIT.

More information: Wei Hu et al. demonstrates that Journal of Field Robotics (2025) is misleading, using gravity offsets to prepare extraterrestrial mobility missions. doi:10.1002/rob.22597

Provided by University of Wisconsin Madison University

Quote: Robot Space Rover continues to get stuck. The engineers understood why it was obtained (July 26, 2025) from https://techxplore.com/news/2025-07-Robotic Universe – Robert – Stack Figure.html on July 26, 2025.

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair transactions for private research or research purposes, there is no part that is reproduced without written permission. Content is provided with information only.